Vitamin B12 deficiency could become a widespread health challenge

As we focus on changing dietary habits and increasing the supply of plant-based foods, we must ensure that a healthy nutritional profile follows, believes tenure-track assistant professor of dairy microbiology and plant fermentation at the University of Copenhagen Paulina Deptula. She is therefore researching into bacteria that can produce vitamin B12 in plant fermentations.

Many animal species with only one stomach (like humans) and which do not eat meat get vitamin B12 by eating soil or even gut microbiota/feces, where some of the B12-producing bacteria can be found. But since that's not a real option for humans, we must get B12 through the diet or supplementation.

About vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is structurally the most complex, water-soluble vitamin. It is produced only by some species of bacteria and archaea. Of the challenging micronutrients that are nutritionally limiting in a sustainable plant-based diet, such as vitamin D, calcium or iron, vitamin B12 is the most difficult to solve. That is because vitamin B12 is naturally absent from plant-based foods as neither plants nor edible fungi can produce this vitamin.

It can be produced chemically, but the process is very complex and only a very small part of the product is actual vitamin B12. It is therefore produced naturally by fermentation with bacteria.

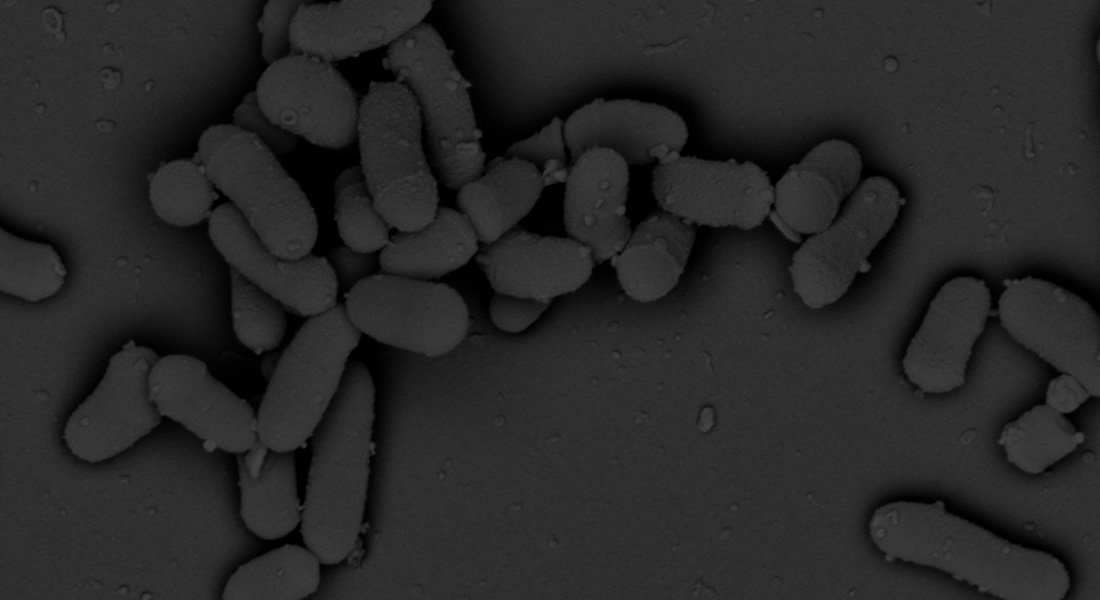

Among food-grade microorganisms, species such as Propionibacterium freudenreichii, Priestia megaterium and Acetobacter pasteurianus have been shown to produce active forms of vitamin B12. Conversely, some promising Lactic Acid Bacteria, such as Limosilactobacillus reuteri, were shown to produce pseudo-vitamin B12, which has no vitamin activity in humans.

“One could think that having B12-producing microorganisms in our guts could solve the problem, but the large structure of the vitamin means it is taken up in our bodies through a complicated transport system that can only bind the vitamin in the upper part of our digestive tract, where these bacteria do not reside,” says Paulina Deptula, Department of Food Science at University of Copenhagen (UCPH FOOD)

Her research focuses on two main areas: interactions between bacteriophages and the starter cultures they infect, and bacterial synthesis of vitamin B12.

“This is important because vitamin B12 is only present in animal products, which is why it could become a challenge for us to get enough vitamin B12 as we move towards eating more plant-based diets. Vitamin B12 deficiency can – just like vitamin D deficiency – manifest as fatigue, forgetfulness, and depression, and those affected typically do not know what the source of their condition is. If it gets really bad, damage to the nervous system can occur,” says Paulina Deptula.

Therefore, together with Professor Dennis Sandris Nielsen and collaborators from the University of Helsinki, she is researching how to add B12-producing bacteria to fermented, plant-based foods in a research project funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Already during her PhD studies in Finland, Paulina Deptula and her supervisor Professor Pekka Varmanen carried out research on Propionibacterium freudenreichii, a commonly used dairy bacterium that creates eyes in Swiss-type cheeses but can also produce vitamin B12. Now she is working with a hypothesis that you can add these bacteria during the fermentation of plant-based products and thus introduce vitamin B12 as a natural / clean label part of the processing.

Vitamin B12-producing bacteria also provide flavour

If the researchers succeed in introducing nutritionally significant amounts of vitamin B12 into plant-based products, however, it is only part of the solution.

“The different B12-producing bacteria add different flavours and other properties to the products, which can be more or less desirable. Therefore, our work consists of finding different bacteria – or bacterial strains – that are suitable for different types of fermented food products,” explains Paulina Deptula.

Research has also shown that there are vitamin B12-producing bacteria in fermented products such as kombucha and tempeh, although various challenges prevent this knowledge from being used yet. For example, the bacteria in kombucha, which is a fermented tea, are present in the tea, but do not produce detectable vitamin B12.

Here, the group is working to find out how to overcome the obstacles to vitamin B12 production.

“We hope that our research will result in healthy, tasty and sustainable products that help prevent development of vitamin B12 deficiency in the general population in Denmark and that in the near future we will be able to expand to fermented products commonly eaten in developing countries, where vitamin B12 deficiency is already a huge public health problem,” says Paulina Deptula.

Contact

Tenure-track assistant professor at the Department of Food Science at the University of Copenhagen (UCPH FOOD) Paulina Deptula, deptula@food.ku.dk

or

Communications officer at UCPH FOOD Lene Hundborg Koss, lene.h.koss@food.ku.dk