Preventing food rot with microbes

An innovative research project led by Henriette Lyng Røder is setting out to prevent soft rot from afflicting our plant-based foods by designing intentional microbial communities and harnessing their interactions to shield the food from the soft rot causing microorganisms.

Around 30% of all food produced globally ends up going to waste. While there are several factors driving this food waste, rot is one of the major culprits. For plant foods, soft rot caused by Pectobacteria, causing them to go mushy and significantly shortening their shelf life, is especially problematic. And with a growing global population coupled with an increased push towards more plant-based diets, preventing as much food waste as possible is imperative.

Having been awarded an Emerging Investigator Grant of DKK 10 mil. by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, Tenure-Track Assistant Professor Henriette Lyng Røder is now setting out to prevent soft rot through natural and sustainable means with her new research project, BIOBARRIER.

“It’s clear that our conventional food preservation methods are inadequate, when roughly a third of the world’s plant-based foods are lost. Right now, we’re trying to clean the plant products, but that opens the door for harmful microbes to settle on the food afterwards. So, we want to design beneficial microbial communities that can be safely applied to our food and that prevent harmful microbes from taking hold,” explains Henriette Lyng Røder.

Positive results from pre-trials

The reasoning is that we don’t have any good ways to keep our fresh plant products free from bacteria. That is why instead of insisting on this tried approach, Henriette’s idea is to take a step back and look at alternative solutions to the problem.

So, instead of letting it be up to chance which microbes settle on our food, Henriette wants to create non-harmful microbial communities whose function is to shield the food products. The first step is to find the right microbes and understand their interactions, so that they can be used as a barrier.

“This project is focused on the fundamentals. We’ll be establishing which bacterial communities are beneficial, discover how they interact with one another, and how the synergistic effects function in practice. We often find that communities of diverse range of bacterial species work better together than by themselves. We also know from pre-trials that it works to protect foods from harmful bacteria, but we still don’t know exactly why – if it’s the good bacteria taking up space, if it’s because of secondary metabolites, or some other effect created from their interactions,” says Henriette Lyng Røder, who also recently received one of the prestigious Inge Lehmann Grants from the Independent Research Fund Denmark.

Shielding from farm to fork

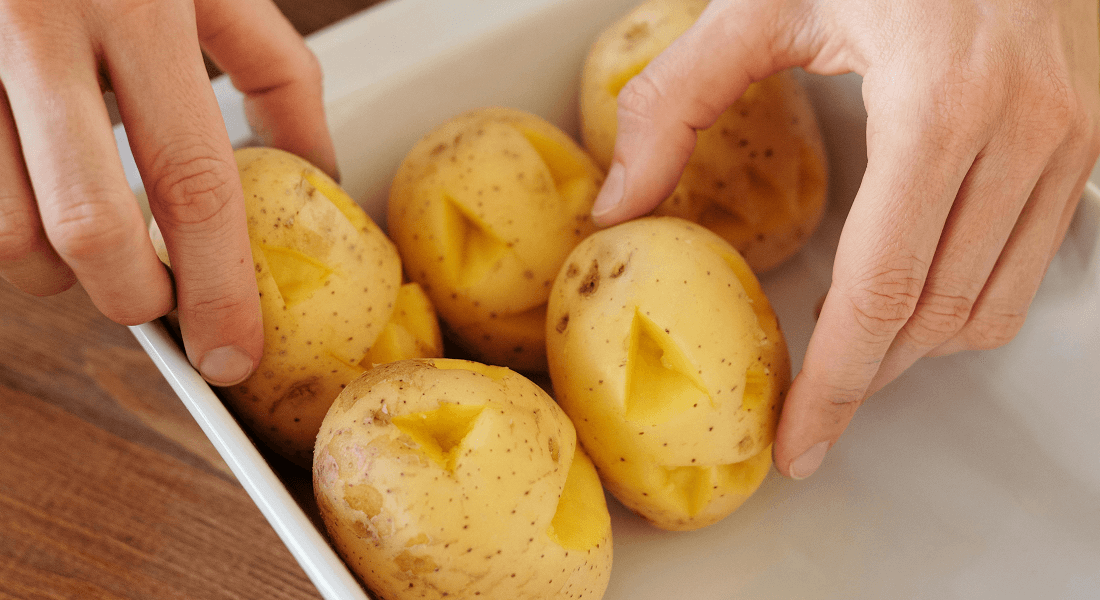

While soft rot can affect a variety of plant foods, BIOBARRIER will focus its research on potatoes, although its results may in time be usable for all kinds of plant foods. The work will be looking to keep the potatoes Pectobacteria-free for both seed tubers, and the end products you can buy in stores. Being able to control our food’s microbiome early is key, explains Henriette Lyng Røder.

“We only have the number of fields that we have, and we need to make sure that plants make it through all its stages to the shelves, and that its shelf life is as long as possible. With seed potatoes, a very expensive part of our production, the breaking point for contaminants is really strict for example, because we don’t want to contaminate the entire chain. That makes it doubly valuable to be able to design and control the microbes on them,” says Henriette Lyng Røder.

She also highlights a range of factors complicating both the assessment of food waste caused by soft rot and what lets the Pectobacteria flourish. Everything from handling – if they get a wound during transport for example – to high humidity and lack of cooling infrastructure may complicate the prevention of food rot. All of which can possibly be circumvented in the long run through BIOBARRIER’s research into the fundamentals of the bacterial communities.

“There are so many factors at play, so we need to better understand the basics of the interactions and then move on to the applied. And it’ll only grow more relevant, because as the temperature rises, bacteria will have a more advantageous environment to grow in. So, we’re both dealing with effects of climate change and the food crisis,” says Henriette Lyng Røder.

Contact

Henriette Lyng Røder

Tenure Track Assistant Professor

h.lyng.roeder@food.ku.dk

Thomas Sten Pedersen

Communications Officer, Department of Food Science

thomas.pedersen@food.ku.dk